Feel good your way: Insight summary 3 - Communicating with young people around physical activity and mental health

Feel good your way

Contents

- Introduction

- Use of Emotion in Marketing

- Communicating with Young People about Mental Health

- Mental Health Campaign Examples

- Communicating with Young People about Physical Activity and Mental Health

- Physical Activity Campaign Examples

- Implications for Campaign

1. Introduction

The purpose of this summary is to draw on existing research since 2017 and create a broad insight into the lives of young people. Whilst this is not a systematic review, it offers a broad picture of young people’s current experiences.

Where available evidence allows, we focus particularly on our audience of interest of girls aged 11-15 in Greater Manchester. The insight from this summary, along with that from our other summaries in this series, engagement with stakeholders, and direct engagement with young people, will inform the creative brief for the GM Moving campaign.

As we have seen in our second insight summary, Supporting Young People’s Mental Health, the mental health and wellbeing of our young people is in crisis; however there is a lot that can be done to support young people to better mental health, with physical activity being an essential tool in our toolkit. Many young people, however, are not currently engaging in sufficient physical activity to reap the mental health benefits, and physical activity is simply not an appealing choice for a significant proportion.

In our final insight summary we will consider the role that effective marketing and communications can play in shaping young people’s perceptions, their feelings, and ultimately their behaviour in terms of physical activity and mental health.

Whilst communications alone will not improve young people’s mental health, what young people see and what they hear around them every day shapes their views and their decisions. This means that communications can influence whether our audience perceive physical activity as something accessible, achievable and attractive for them; or as something elitist and only for a certain kind of person. Communications are therefore a key part of an overall system approach.

2. Use of Emotion in Marketing

We saw in our previous insight summary that young people in general recognise the health benefits of being active, with a significant majority saying they would like to do more; and yet more than half are still not reaching the recommended levels.

Many of the reasons which sit behind this stem from the fact that our day-to-day decision making is driven much less by long-term, rational thinking about what we should do, and much more by immediate rewards and how something will feel right now (known as temporal discounting; Nature, 2022).

A study by Segar (2016) identified various issues with the way physical activity is presented to patients by healthcare professionals which limit patient uptake. It reports that framing physical activity as a something that should be done for better health, rather than something enjoyable is not attractive to patients. Emotions play a significant role in driving everyday decisions, including physical activity; so anticipation of positive emotions make something attractive and vice versa.

They also report that there is an intensity threshold for exercise at which positive emotions become negative for most people; so selling regimes of hardcore exercise with no pain, no gain mantras is generally counterproductive, particularly for those who are currently least active.

In marketing circles, this power of emotion has long been widely recognised, with emotional marketing making up the core of countless successful campaigns. Professor Robert Heath, of Bath University, said: “Successful brand-building advertising is 99% subconscious seduction, 1% conscious persuasion" (WARC, 2016)

Marketing guru, David Ogilvy, said in his book that a rational reason married with an emotional connection creates the most effective marketing (but that you should not attempt either if you can’t deliver).

An example where this approach has been demonstrated is in Dove’s Campaign for Real Beauty. In 2004, by responding to women telling them that beauty marketing which sells a vision of perfection and never ageing made them feel insecure, Dove transformed their brand position overnight. This is still their overarching approach today, for example, Project #ShowUs responds to the fact that 70% of women say they don’t feel represented in the media.

3. Communicating with Young People about Mental Health

Mental health can be a challenging topic for many of us so it is important to approach it in the right way. In order to connect with girls, we need to be able to engage with them in a way that works for them, using effective and appropriate messages, messengers, resources and channels. There are a number of online guides on how adults can talk to young people about their mental health which can help us to shape our thinking. For example:

- Young Minds: How To Have A Conversation With Young People About Mental Health.

- Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families: How to start a conversation with children and young people about mental health.

- MIND: Talking to a young person about their mental health.

- Beyond Blue: How to talk about mental health with a young person.

The overarching approach in each of these includes:

- Choose a time and place that is calm and comfortable, but it doesn’t have to be perfect – there will never be a perfect time.

- Plan how you’d like to start the conversation – choose an open question which is non-judgemental and use a calm tone.

- Listen and keep an open mind.

- Reassure them that their feelings and experiences are valid.

- Reassure them you’re there to support and ask how they’d like to be supported.

- Be honest.

- Don’t try to fix everything.

- Don’t force things if they aren’t ready to talk, but leave things open so you can try again in the future.

Peer support can be equally important for young people’s mental health. A review of the evidence by the Department for Education (2017) found mixed evidence for the effectiveness of peer support schemes, however said that in the right circumstances they could deliver positive outcomes. This is echoed in research by the Centre for Mental Health (2020) who found that positive peer relationships are a key protective factor for positive mental health in children and young people.

“Done properly, it can bring a unique and sustainable benefit to children and young people’s wellbeing, that can endure into adulthood.”(Centre for Mental Health, 2020)

For our campaign, co-creation is a key element and we anticipate young people will feature as the messengers within the campaign. Again, there is a range of guidance available for young people wanting to support each other:

- Mind Guidance for young people on supporting a friend.

- Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM): Guide to looking out for a mate.

Themes here are similar to those for adults, however there is additional emphasis that young people should look out for their own wellbeing and not try to take everything on themselves. They also suggest that checking in regularly and doing something nice for someone or spending time together can be a good way to show support.

In Australia, one study (Thorn et al, 2020) worked with young people, age 18-25, to co-design a campaign around online support for mental health and suicide prevention. The young people reported:

- Wanting tools that would give them autonomy to take care of their own mental health.

- Visible links to support services when these were needed.

- Being inspired by real stories of hope and recovery.

- Did not necessarily want to identify online as needing support.

- That talking with a friend or peer was often the best first step in seeking support.

They said the campaign itself should:

- Feature real people.

- Be representative of diverse young people.

- Include accessible content, e.g., subtitles, translation.

- Be available on social platforms they already used.

- Animation was a popular option, however, should still have an element of realness and not use unsuitable mascots, animals, or memes which could be seen as too flippant.

4. Mental Health Marketing Examples

There are a wide range of existing campaigns around mental health which can give us inspiration for what works in this space. Although note that not all of these campaigns are youth specific and some of these examples deal with difficult themes, such as suicide, so may want to consider what is most appropriate in the context of our campaign objectives.

Health Foundation, Mental Health Awareness Week,

Mind over Mirror Campaign, 2019

- NHS Every Mind Matters: Youth Mental Health Tips: Includes 6 videos with tips on a variety of topics from youth influencers.

- Mental Health Awareness Week is hosted every May by the Health Foundation. Each year has a theme e.g. 2021 was Nature, 2019 was Body Image. There are various downloadable resources available, which were co-designed with young people and parents, to help promote each week. An example from the 2019 Body Image campaign is shown left.

Dove, The Self-Esteem Project, 2004-

Dove’s more recent work with The Self-Esteem Project has focused on girls’ mental health, based on the insight that one in two girls say toxic beauty advice on social media causes low self-esteem.

Dove, Detox Your Feed Campaign, 2022

An example is their recent Detox your feed campaign, which highlighted the kind of toxic messaging about appearance and what is supposedly beautiful that adolescent and teenage girls are seeing every day through social media. It encourages girls, with support from their mums, to unfollow negative influencers.

Dove, #TheSelfieTalk, 2021

Dove also ran related content around the pressure on young girls to present perfect selfies on social media and encouraged parents to have #TheSelfieTalk.

Always, Like a Girl, 2014

Always started a fantastic campaign, Like A Girl in 2014 which focuses on girl’s self-esteem by highlighting the negative impact of stereotypes around what girls should be like and what they can do. The campaign is still running today and has since been backed by Game of Thrones star, Maisie Williams, to continue spreading the message.

The Football Association, Heads Together, 2019

In 2019, Heads Together and FA produced the Heads Up campaign, using big stars from across the world of football promoting mental health as just as important as physical health.

CALM and Topshop/Topman, #LetWhatsInsideOut Campaign, 2019

In partnership with CALM, Topshop/Topman introduced Self-care labelling in 2019 for a range of clothing. Havas and CALM team up to create self-care labelling for Topshop and Topman (campaignlive.co.uk) Clothing care labels reimagined for wellbeing in Topshop x Calm’s Care Sewn In range (itsnicethat.com).

CALM have also undertaken a number of hard hitting campaigns around the topic of suicide. For example, Suicidal Doesn’t Always Look Suicidal, designed to break the silence and smash the stigma around suicide to get people talking about it.

Whilst we are unlikely to tackle the issue of suicide specifically in the campaign, it does show the power of using strong visuals to land an important message.

Young Minds, Wise Up, 2019

Young Minds commonly feature young people in their films and have a range of assets, such as this one on what self-care means, which ask young people to talk about mental health issues in their own words. Although more targeted at education institute than young people themselves, in 2019 Young Minds launched the Wise Up campaign to encourage the prioritisation of mental health and wellbeing over academic achievement. In 2022 the fight continues with the #EndTheWait campaign, which saw Young Minds deliver a card to the Secretary of State outlining the change they want to see for young people’s mental health.

5. Communicating with Young People about Physical Activity

How we talk to young people about physical activity is just as important as how we talk about mental health. We want active opportunities to feel like safe spaces where young people feel supported and like they belong.

Research from the University of Bristol (Nobles, 2020) looked at people’s preferences in physical activity communications and builds well on the research from Segar (2016) highlighted in Section 2.

They found:

- Young people (11-15) place more emphasis on the enjoyment, well-being and mental health benefits, with physical activity being described as “providing a feel good factor”. Physical activity as an opportunity for social connection was seen as important by all groups.

- All groups reported that the language used should be simple, non-academic and jargon-free, highlighting the need for the ‘translation’ of the language used in the UK physical activity guidelines, which was largely perceived as inaccessible by all groups. Words such as aerobic, intensity, and sedentary were identified as words to avoid, as demonstrated through this quote:

“I thought sedentary was some kind of rock.” (Children and young people’s workshop)

- Messages should be invitational rather than instructive, avoiding the sense of being told what to do. Children and young people wanted language that was “snappy”, “chatty”, “friendly” and “encouraging”.

- The groups suggested that a variety of mechanisms are needed to deliver the message. All groups preferred visual mechanisms, and suggested that multiple mechanisms (e.g., social media, TV, posters) be used to both increase the reach of the message (due to seeing the message in many places) and to reinforce the message (due to a consistent message being communicated). Social media channels (such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Snapchat) as well as YouTube, streaming platforms, podcasts, apps and video games were mentioned by young people as potential vehicles for the message.

- For children and young people, celebrities were seen as effective messengers because of their perceived status and influence in society. However, these celebrities may still need to “look like me” in order for the message to resonate. All groups agreed that messengers should be trustworthy and influential.

The Framework Institute (2020) have also explored the challenges and opportunities around physical activity communications and highlighted five general issues with the way the public perceives the messaging it sees and hears around being active. GM Moving have previously highlighted four of these as key and these will be relevant to our campaign.

The research found that people:

- Have a narrow understanding of physical activity only as vigorous exercise

- Tend to assume that a person’s willpower and inner drive shapes whether they are physically active

- Tend to adopt a “no pain, no gain” perspective on being active

- Think physical activity mostly happens in dedicated workout spaces

These perceptions can lead to a narrow view of what being active means and who it is for. This exacerbates a sense of not belonging in active environments and not feeling being active is for people like me.

6. Physical Activity Campaign Examples

There are a wide range of physical activity and sport marketing campaigns available, in fact it is one of the most popular topics for brands to associate themselves with. Here we have therefore focused on those examples which are specific to young people’s experiences of physical activity, particularly girls, and speak to creating a sense of belonging through positive and welcoming environments.

Local pride

- GM Walking’s 2020 The Greater Manchester Way film tapped into Manchester pride and a sense of this is how we do things round here.

Inclusive spaces

- Parkrun are keen to promote themselves as a space which is genuinely inclusive for everyone to take part, so this myth busting film from 2018 set out some perceptions versus reality using comedy to good effect.

- Stonewall run their annual Rainbow Laces campaign every December which encourages sports teams and groups to wear rainbow laces to show that their club, session or group is a welcoming space for LGBTQIA+ people. It is supported by both elite and grassroots organisations.

- In Don’t Retire Kid, ESPN wanted to highlight that many children and young people were dropping out of sport due to the pressured environment and feeling like it was no longer fun: “I said I’d play this game as long as I was having fun, and now it’s time to go."

Empowering women and girls through sport and physical activity

Below are some examples which showcase women and girls as very much belonging in and thriving in the world of sport and physical activity. Although it is important to need to be thoughtful around how we use this type of messaging. Some examples, particularly those including elite athletes, can be very emotionally powerful but ultimately unattainable for our audience so unlikely to elicit behaviour change.

- Nike is a regular supporter of International Women’s Day, highlighting the successes and achievements of elite female athletes. This example is from IWD 2020.

- Dream Crazier highlights elite female athletes who have broken boundaries, in spite of being told they couldn’t.

- The multi-award winning This Girl Can campaign from Sport England was seen as a game changer in marketing sport and physical activity to women and girls. It showed for the first time real women and girls who were working hard and were sweaty and had “jiggly bits” but, importantly, were having a great time.

- This Girl Can has since inspired a wide range of local interpretations, with this one from Cumbria a particularly good example of adhering to the campaign principles whilst stamping a sense of local pride on the output.

Using physical activity to support better mental health

Whilst our campaign may be a first in terms of promoting physical activity for young people’s mental health, there are a number of examples of promoting being active for mental health to a wider audience.

There are a number of running initiatives, such as RUN TALK RUN which advocate for running alongside talking as a therapy for better mental health. RED January specifically promotes running (or more recently walking or moving in any way you like) to beat the winter blues by being active every day in January. They have a school activity pack.

In 2021, Asics worked in partnership with Mind to use physical activity to uplift the mood of a whole town. This one day festival style event gave a 27% mood uplift. The campaign could be seen as a bit gimmicky as it was only for a day, however something like this can be used to raise profile of other activities as part of a wider system approach.

Building on its commitment to physical activity for mental health, Asics have also created the Mind Uplifter. It is an online tool that measures your mood based on a photo, then asks you to exercise for 20 mins, before taking another photo. Face analysis is used to tell you how your mood has changed.

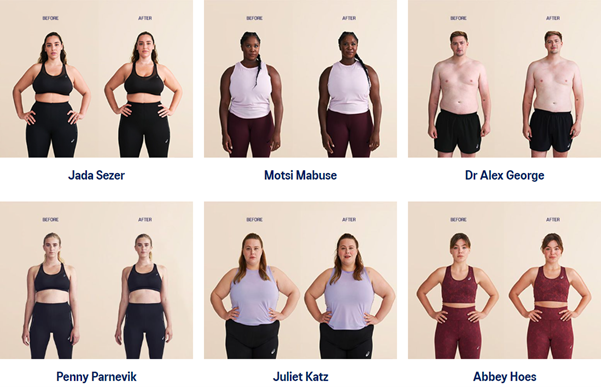

In 2022 Asics also launched their Dramatic Transformations campaign for Mental Health Day, which highlights the damaging effect of unrealistic before and after photos which suggest the main reason to exercise is to transform your body. They instead promote the before and after shift in mood from just 20 minutes of exercise.

#TimeTogether is a campaign from Women in Sport encouraging mums and daughters to use sport and physical activity as a way to spend time together. It was refreshed in 2022 following the 'summer of sport'.

It is also helpful to take into account the following guidance on inclusion:

- Activity Alliance Inclusive Communications Guide For Disabled People.

- Stonewall Rainbow Laces Lesson Packs for including LGBTQIA+ in sport and physical activity in schools and colleges.

7. Implications for Feel good your way

- Communications which create a positive emotional connection with the audience can be a powerful tool for behaviour change.

- Language around mental health should be honest, open-minded, non-judgemental and reassuring. It should demonstrate to young people that their experiences are valid, and be realistic, not trying to fix everything or say everything will be fine when it won’t.

- The benefits of physical activity for mental health should be presented as about enjoyment, wellbeing and the ‘feel-good-factor’. Physical activity should not be presented as something young people should’

- A range of activity types and settings should be presented, to break the myths that only certain types of activity, like running, sports and going to the gym, are proper exercise and that these have to be done at high intensity and in a dedicated active space to count.

- The campaign should also feel empowering for our audience as young girls can still feel excluded from sport and physical activity and like they don’t belong there. This can be linked to a sense of local pride and this is what we do round here. Although caution should be exhibited not to present sport and physical activity as unattainable.

- Plain English should be used and in particular we should avoid the use of academic language such as that found in the Physical Activity Guidelines. Young people prefer language to be snappy, chatty, friendly and encouraging.

- Humour or a more light-hearted tone can be used to gain engagement, but not at the expense of appearing to make light of important mental health issues.

- Messengers will be key with a preference for role models who look like me.

- A range of channels can be used, however social media and shareable content will be key for our audience.

We should think carefully, and discuss with our youth advisory group, the extent which we want the campaign to touch on particularly difficult topics such as suicide, and if yes, how we approach this sensitively and realistically.

NB. This insight report was produced by Proper Active as part of the Feel Good Your Way campaign.

8. References

- Centre for Mental Health (2020) Peer support models for children and young people with mental health problems

- Department for Education (2017) Peer support and children and young people’s mental health

- Framework Institute (2020) Communicating about Physical Activity - challenges opportunities and emerging recommendations

- Nature (2022) The globalizability of temporal discounting

- Nobles (2020) “Let’s talk about physical activity”: Understanding the preferences of under-served communities when messaging physical activity guidelines to the public

- Ogilvy (1983, reprinted in 2018) Ogilvy on Advertising

- Segar et al (2016) From a vital sign to vitality: Selling exercise so patients want to buy it

- Thorn et al (2020) Developing a Suicide Prevention Social Media Campaign With Young People (The #Chatsafe Project): Co-Design Approach

- WARC (2016) What we know about using emotion